We Don't Learn from Winning (AiQ Insights)

Bonus: This Week's AI Controversy Is Only the Beginning of the Conversation

One of the first stops in my trader trainee rotation was a commercial Midwest trading desk. The head trader—let’s call him John—was the director of all things risk. He held the P&L responsibility and ran the show, as was typical of that era.

John had earned his MBA from the University of Chicago, where I had taken a number of classes while clerking at the Merc (CME). We hit it off quickly.

John was an early riser. He told me that if I were at his desk before the day began, he’d give me projects and take time to answer my questions. This was back when research was still largely manual—from collecting raw data to running anything more than basic statistical analysis.

I learned the janitors’ schedules for those three weeks, arriving right after. Like many of the traders I looked up to at the time, John would eventually go on to run a fund. As my three-week rotation wrapped up, he pulled me aside.

Nick, here’s how this deal works. You need to ask all your questions now because in the future they’re going to expect you to know the answers. When you are running a desk you don’t get to ask dumb questions. You are the guy who needs to have the answers. Each trader you meet and desk you sit on, ask your questions now. You won’t get to again.

It wasn’t until years later that I fully understood the politics—and the quiet resentment—that brewed in a bureaucracy trying to operate like a hedge fund. John, like many successful risk-takers, was especially self-interested. He didn’t waste time on trainees.

That’s why his words stuck with me. They meant something. I didn’t realize it then, but making that effort to share probably meant something to him, too.

Losing is Part of the Job, an Important Part

Recently, I came across a post that brought me right back to those early days—the sting of my first real losses, the weight of a trade gone wrong, and the quiet reckoning that follows. These moments either harden or send you in search of another career path.

To PositiveDrift_, the young man who shared his loss publicly: keep your head up. It takes real courage and humility to do that. And those traits will serve you far better than the “degen” culture of Reddit ever could. If you're serious about building a career in markets, this is how it has to be.

Here’s a fact every student of trading must internalize early: losses feel worse than wins feel good. That’s loss aversion, and it’s deeply human. Don't fight it, learn from it.

Your first goal isn’t to make money, it’s to stop losing it. Capital preservation comes first. Risk management and emotional discipline become the foundations. Successful traders carry scars. They’re the mark of someone in the game, learning, and evolving.

For the sake of full disclosure, I’ve messaged with this account in the past and believe he’s a hard-working young man, trying to absorb the harsh lessons of the market as a side project. It’s a tall order, even more so when it’s not your primary focus. We wish him luck, and we gave him a free subscription.

See? Things are already looking up. 😉

The truth is simple: you cannot make it as a trader without the capacity to recover from large losses. You won’t get close to a serious role in markets without learning the lessons that only losing real money can teach.

Not theory, not paper trading—just pain. All traders know that feeling of needing to retch in the trash can under your desk. Your bonus is gone, and possibly your job next. Then, if you’re paying attention and willing to get up after being knocked down—the wisdom that follows.

Path this, one only for you.

-Trading Yoda

Small Losses Get You Ready for the Big Losses

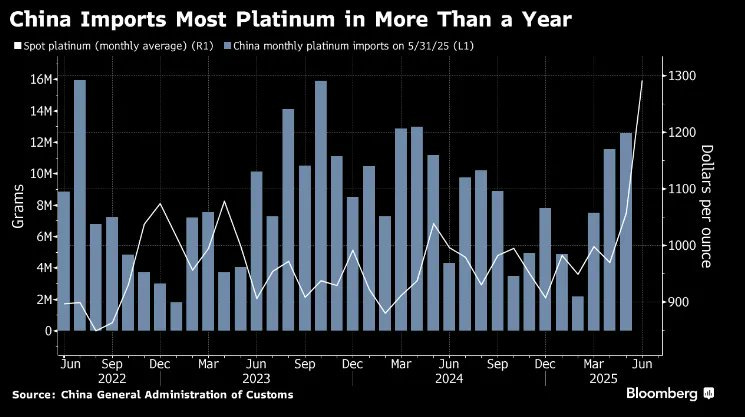

A few months back, I mentioned that platinum looked ready to break out—and that I’d certainly miss the big trade. No surprise there. It was only a matter of time, and if there’s one thing I’ve experienced, it’s that markets have a foul sense of humor.

Now, I see analysts calling for a top just 30 days into a multi-decade breakout. That alone makes me think we’ll see platinum trading north of $2,000 this time next year. It sounds like a stretch—until you remember the Chinese affinity for shinier metal. Under-owned and persistently disappointing, yet one of the few hedges to a world fueled by unconstrained deficit spending—a classic setup for a multi-year trend.

In that same article, I mentioned my first real loss. I had gone home long between 20 and 40 contracts of soybeans and soybean meal. I can’t recall the exact total. What I do remember, vividly, is checking my phone on Sunday night and seeing the market was limit down. I scanned the headlines. What is Swine Flu? I remember my first thought. We would not have pigs to feed soybean meal to anymore. To be young and dumb.

I sprinted to my computer. At one point, I was staring at a $65,000 unrealized loss. That suggests the position was around 35 contracts—comically small in hindsight, but absolutely massive to me at the time. I showed up to work Monday morning in a cold sweat. I had lost 70% of my annual salary within the first 72 hours of opening my PA (personal account).

The Closest I Have Come to A Risk-Free Arb

Less than 18 months later, I was managing the futures risk and speculative book for one of the company’s processing businesses. While my official title was too junior to report directly to John, he became my de facto boss. We messaged frequently about trades, mostly when to size up if I thought the opportunity was worth his itme. His guidance never wavered: If you can make more money—do it.

At the time, I had discovered what felt like the holy grail of trading, a relatively risk-free arbitrage. You have to understand the context: this was during a brief window when most of the volume had migrated to electronic platforms, but global markets were not yet 24 hours. Here were a few of the inefficiencies:

USDA reports were released while some markets were closed and others open.

Time zone mismatches created periods of less liduity.

The US had enacted biofuel policies that made Canadian assets exponentially more valuable (sound familiar?), but Canadians had no idea how this worked, yet.

I realized I could trade the USDA reports aggressively. I needed to put on about 12,000 tonnes per day of board crush/board margin to keep up with usage. This allowed me to hedge against our physical business while knowing that the company would be pleased to take on ownership at better margins if the markets overshot.

The exchange had two structural flaws with its electronic contract. There was another flaw in delivery, but that’s a story for a different day:

The price limits were too wide, discouraging traders from placing resting orders in the overnight market.

The contract size was too small, creating a mismatch relative to CBOT products without ample liquidity.

The opportunity was large orders during illiquid periods.

A 200 or 500-lot order could move the market to its limit. If I hit the screen with 1,000 to 3,000 contracts, I could push the price to its limit and fill resting orders I’d already placed. These contracts were too small to do serious P&L damage unless someone big was willing to take the other side. This was an acceptable risk because others would follow me as margins expanded or contracted.

It’s still a lot of money. Didn’t the company have limits? Yes, but my brokers didn’t.

I could put limit resting orders, knowing these would likely converge back during the morning session once Western Canada was awake. At the time, a not insignificant portion of the offices were still on the West Coast. Of course, the full limit orders never got completely filled. That would’ve been a true free lunch—and those don’t exist. At least not for long.

Tangent: Years later, I became friends with the CEO of the exchange, and met the head of compliance. Back then, I’d built a bit of a reputation as a problem child. In my defense, I did get on committee calls to point out the contract’s flaws.

They ignored me, oblivious to how we were making money. Most exchange members were in their 60s—comfortable, complacent, and utterly unaware of how quickly the industry was evolving. It was the biofuel boom, and everyone was printing money. No one cared. No one ever does until the margins disappear.

Things were going well, and my confidence was sky-high, which is how the story of every significant trading loss begins.

Are You Going to Make it Back?

My speculative book was making money, and John had quietly let me know that if I kept it up, he’d make sure I participated in the bonus pool. That was the holy grail at a commercial. Trader speak for being “made,” like making a partner at a law firm or being invited into an exclusive club. Eat what you kill. Every profitable trader’s dream.

It was one thing to arb Canadian mispricings with a physical backstop. It was another thing entirely to start pressing in Chicago.

It was a Thursday. I had built a sizable position in oilseed products. I didn’t know much about South America, but I was coming of age during the China boom. I liked to play from the long side. My instinct was that the South American supply scare was the next catalyst to propel pirces higher.

I got caught long and wrong.

I felt sick. I nearly threw up in my trash can. I looked around the office. Business as usual. No one seemed to notice how f&%$ing irrational the market felt that day. How could this be happening? I had just given back the first three months of my year in a single day. Nobody around me had a clue.

I liquidated the entire position. It was close to $1 million in my PA, and began to imagine the conversations where I would attempt to justify my arrogance. I took Friday off and went camping. I needed to clear my head.

When I got in early Monday morning, I felt better. I hadn’t checked my emails all weekend. This was early days of the 24/7 connectivity. It was still acceptable to wait until Monday.

About an hour into the session, I messaged John. From what I remember, the exchange went something like this:

N: “Hey, how’s it going. Rough end to the week for you guys, too?”

J: “Yeah”

N: “Any thoughts on markets or positions?”

J: “Not really”

N: “Any rumors or crop updates? Anything stand out this week?”

J: “Nick, what’s up? Why the messages?”

When we messaged, it was about positions and action. I would tell him when I saw a trade that could be put on in size. No small talk. No beating around the bush.

N: “I am not sure you noticed, but I lost $1 M in my PA.”

J: “Yeah. I saw it.”

N: “Are there any concerns or issues? Anything you want to know?”

J: “Are you going to make it back?”

N: “Yeah.”

J: “Then why are you bothering me with this?”

That was it. I made it back.

I learned more from that single loss than all my winning trades over the prior two years.

Overconfidence walked me straight into the trap. Then came the trader’s spiral: the panic, the self-pity after all the hard work wasted, and the imaginary conversations with bosses and risk managers. All of it distracted from the only job that mattered—get flat and start making money again.

What felt like an insurmountable blow at the time was just another step toward becoming a real trader. Every pro talks about discipline, but losing money is how we come to embrace it.

There is no secret sauce. The process doesn’t waiver.

Cut your losses. Get a clear head. Start fresh. Get back to making money.

AI Controversy & My Reuters Thesis Gains Traction

This week’s X clickbait AI controversy pushed me to think more deeply about the consequences of companies and individuals chasing the lowest-hanging fruit AI offers.

The changes in journalism, data analysis, and risk management are still in the early innings. Agriculture will be one of the last industries to catch up. Many will resist—or try to ignore it altogether. AI will reduce headcount, cut costs, automate repetitive tasks, and make content easier even for the most non-technical owners.

The gains for bad behavior may be even greater early in the AI adoption cycle.

But if you catch yourself thinking, “I can retire soon enough, this isn’t for me,” that’s a mistake.

This is exactly why AiQ is building solutions. Big data, AI, and machine learning tools will soon put answers at your fingertips. You’ll no longer have to wonder whether an “analyst” is doing real work or just chasing headlines. We’re going to make it more useful—and more affordable—than the services you’re paying for today.

Our Thesis Has Us Thinking Deeper—More to Come

In the coming weeks, I plan to develop a broader thesis around the blunt-force rollout of AI—specifically, the in-your-face implementation we’re seeing across content and media platforms.

This may actually explain why I’ve come to view Reuters as a reliable contrarian indicator. Here’s a company with seemingly limitless resources, and yet its authors don’t appear to meaningfully engage with the data they cite. Instead, they churn out takes that seem perfectly timed to top-tick prevailing sentiment, week after week.

What used to be analysis framed as journalism for professionals—now feels more like hashtag-chasing with a byline.

Here are some quotes from the article. If you didn’t know any better, it would appear the US is about to harvest one of its worst wheat crops ever.

Farmers cut their losses early this year across the U.S. wheat belt, stretching from Texas to Montana. They were choosing to bale the wheat into hay, plow their fields under or turn them over to animals to graze. In Nebraska, wheat acreage is less than half of what it was in 2005…

Interviews with more than a dozen farmers and analysts across Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma, along with a review of U.S. Department of Agriculture data, revealed a vast disparity in profit for wheat compared to other crops. This has led farmers to abandon more fields before harvest.

US yields will be near records. This article makes me want to stock my basement with pasta and freeze loaves of bread.

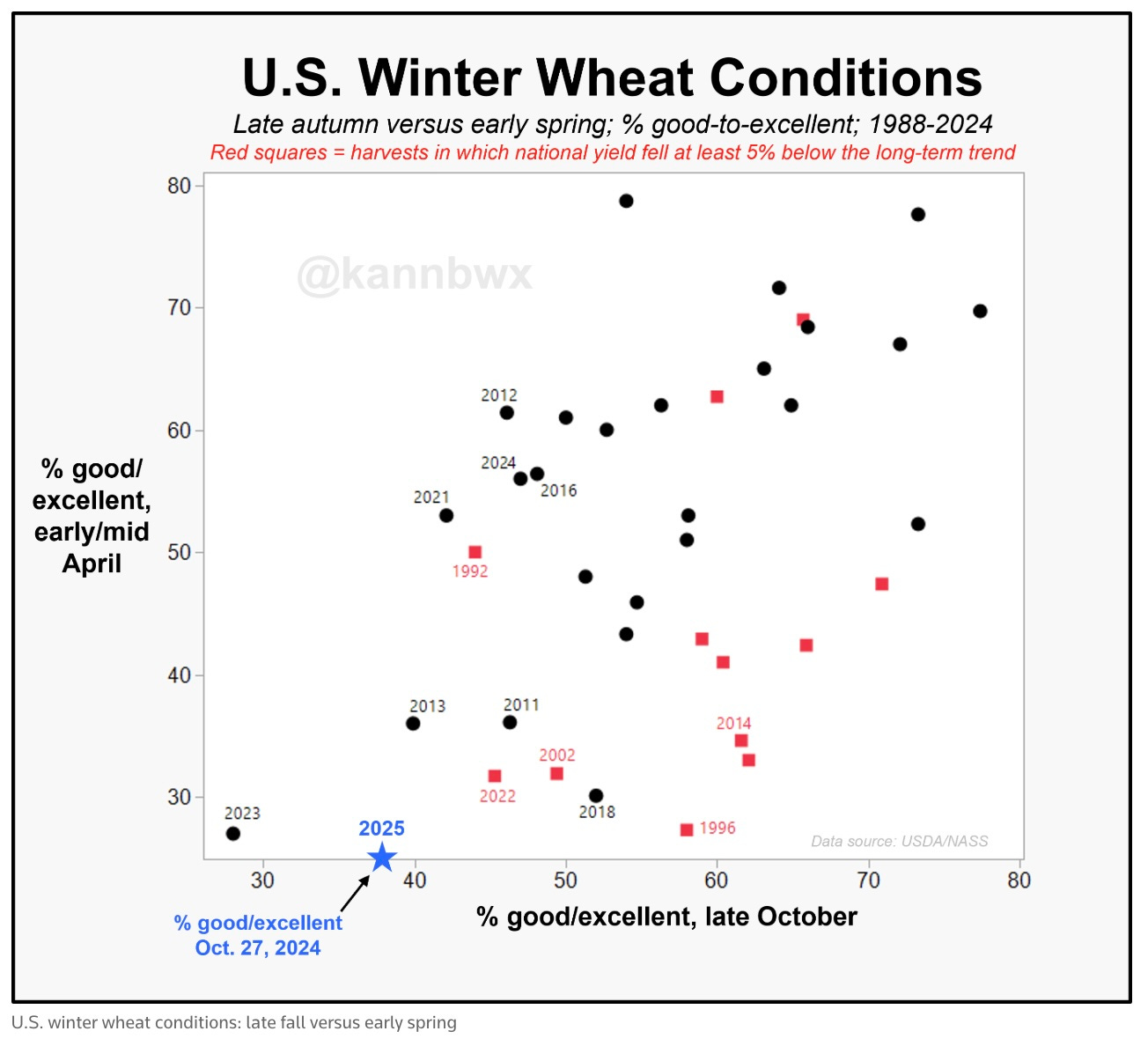

Let’s revisit Reuters’ reporting on this same crop from the fall. I flagged it at the time for two reasons. First, it was misleading—there’s no meaningful relationship between fall field conditions and final yields. This assumes the goal is to make money, not read about things that may or may not matter—flip a coin.

Second, 2023 turned out to be one of the best years on record. You’d never publish a headline like that if you’d done even a basic dive into the data. The only analysts who were stumped were the ones not doing the most basic analyst work. Unfortunately, this reporting type is becoming increasingly frequent.

Thank you for reading. Please reach out to Nico@archaiq.ai with any suggestions on how to improve our products or if you're interested in exploring new opportunities with ArchaiQ. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter at www.archaiq.ai.

This is not trading or investment advice. Trading Futures is a high-risk activity; please consult with a professional.