Let's Talk About the Debt. Inflation is NOT High Prices or a Monthly Calculation (Part 2)

How Inflation, Debt, and Politics Collide in the Late Stages of the Cycle

Why a Series on Inflation?

It’s a fair question. AiQ operates at the intersection of artificial intelligence, big data, and meteorological analytics — but why this focus on inflation?

Because the deflationary era powered by cheap technology in America and the developed West is over. Robotics and AI will boost productivity, but ongoing deficit spending means these societies have little intention of living within their means (more on that below). This shift touches everything — from the cost of crop inputs to the signals driving machine-learning models that automate trades.

Inflation has reshaped the world we operate in, and understanding how—and why—is now essential to adapt. When you understand that maintaining your edge requires constant growth, AiQ is ready to deliver.

An AiQ Maxim: To protect our businesses and maximize profits, we must know where we are in the economic, inflation, and debt cycles.

Why Do Politicians Want Lower Rates?

Let’s begin by examining how markets assign value. At the core lies the so-called risk-free rate, a foundational benchmark that permeates every corner of finance, yet we rarely give it two seconds of thought.

Whether embedded in the Black-Scholes model when pricing options, factored into the cost-of-carry when storing agricultural commodities like corn and soybeans, or influencing asset allocation strategies in your 401(k), the risk-free rate quietly governs financial theory and household behaviors.

We instinctively understand that higher returns demand higher risk. But what does that risk really need to cover? At its essence, it must compensate for two real-world threats:

A) The possibility of losing capital

B) The erosion of purchasing power due to inflation

Imagine being offered an extremely safe investment—no loss of principal—but yields just 2% annually, while your cost of living increases by 3.5%. You’d decline the offer, and rightly so, probably wondering about the future of that salesman.

The counterexample to this is crypto’s appeal. You can make generational wealth and escape the inflation trap with one big bet. The worst case? Lose the principle. Who wants to toil a 9-5 when that’s an attainable outcome the President is promoting? It’s oddly logical to bet the house. A red line traders should never cross, but it is difficult to argue against in the era of Trump 1.0-Biden-Trump 2.0.

Inflation expectations are embedded into virtually every financial model and human decision. As inflation rises, we must generate higher nominal returns just to stand still. This goes far beyond the headline CPI numbers reported by governments, or exogenous shocks like COVID-driven fiscal expansion, war-related supply chain disruptions, or tariff policies.

In this context, it’s clear why politicians favor lower interest rates. Debt payments come straight off the top, and by pushing down the yield curve, they can extend maturities, lock in lower costs, and shift more spending toward growth—an attempt to outrun the inflation trap. But as we show, there’s a floor beneath which the risk-free rate becomes unsustainable, setting up a growing tension between governments and the private sector.

Part I of this series referred to it as purchasing power destruction. The subtle inflation metastasizes like an out-of-control cancer. That is the inflation we care about, and that is the inflation shaping everything from crop insurance decisions to capital allocation across the supply chain.

This is the inflation that results from fiscal dominance, currently driving policy makers in Washington, and nominal growth at all costs, the administration’s new plan A, B, and C. The consequence of this framework dominating policy is that debt will balloon.

But Nick, hasn’t it already?

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet!

Before we jump into the meat of this note-debt and why it matters-let’s dispel a simple notion. We cannot simply refuse to pay the debt or cut rates to pay a lot less, as our President suggests. The US is like the Lannisters in that they will always pay their debts—granted, the Lannisters meant this literally and as a cleverly veiled threat.

Only once we accept that Washington will pay its debts do we begin to grasp the consequences for society and markets. The insidious nature of inflation, resulting from mounting debt, is a freight train we cannot stop. Lyn Alden has written extensively on this. I suggest looking her up here.

Here is why default is a foolish fantasy.

It’s Likely Unconstitutional

The 14th Amendment states that the “validity of the public debt... shall not be questioned.” Default would plunge the country into a constitutional and legal crisis, not just an economic one.It Would Shatter Global Confidence

The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency hinges on trust. While political rhetoric already rattles markets, an actual default would trigger a collapse in credibility. An analogy is that Trump’s Fed independence attacks are a small bomb, while public default is the nuclear option.Americans Would Pay First — And the Most in the Long Run

The largest holders of U.S. debt aren’t foreign adversaries—they’re institutions like Social Security, Medicare, and the Fed. A default would hit retirees and workers much harder than Chinese citizens. While the Fed doesn’t need the income, US Entitlements 100% do — this is as they fall even further in debt.

Knowing we cannot default, consider now Trump’s premise that we cut rates aggressively, possibly taking the risk-free rate below 3 to 3.5%—my opinion on a fair gauge for where inflation is running for the Middle Class. It’s certainly higher for the poor and lower for the rich — one of the many benefits of being wealthy with regressive tax proposals.

Since We Will Not Default, We Choose Inflation

There are two types of people: those who believe in God and those who think they are God.

-C.S. Lewis

This quote reminds me of every politician in history who thought they could manipulate the money supply and control the cost of capital. While we are often critical of the arrogance of the current administration, there are valid reasons that even worst-case scenarios need to be avoided.

All governments err on the side of inflation. The threat of a debt deflation spiral is too great a risk. Many economists attribute the duration and severity of the Great Depression to recognizing this too late.

Irving Fisher, one of the most prominent economists, developed the debt-deflation theory about Booms and Depressions, explaining how deflation exacerbates an over-indebted economy's debt burden. The defaults of citizens and businesses lead to economic contraction, which destroys the confidence and any chance to generate enough economic velocity to escape the negative feedback loop. This is the economic bogeyman that all policy makers fear when staring down the barrel of a late-stage debt cycle.

My rebuttal is that we are not at the point where policymakers risk losing control, so this is not a valid counterpoint. However, tuck it away for future reference because it could become the default excuse when Federal debt/GDP reaches the more critical 120% to 130% range.

This is why inflation isn’t an accident, and is not going away. It’s the path they've chosen. Chosen. Past tense.

Now that we’ve accepted the US won’t default and will not cut spending, let’s discuss the current debt makeup of the US.

There are a few misconceptions. The first one is that the US has unsustainable debt levels at the government and individual levels.

What Makes Up US Debt? Public vs Private

Total Personal debt in the US is over $18 trillion, broken down as:

$13.5 mortgages and home lines of credit

$1.6 Auto Loans

$1.6 Student Loans

$1.2 Credit Cards

$.5 Other

While the raw numbers are large, most of the U.S. household debt is tied to home ownership, and the burden of that debt has declined as a share of disposable income. That’s the proper lens: debt should be measured relative to a household’s ability to service it. By that standard, the financial strain has eased for many, despite headlines suggesting the contrary. Household debt levels may look massive in nominal terms, but relative to income, they’ve become more sustainable since the Pandemic. See that word nominal again?

Household and consumer debt levels appear manageable on the surface. Household debt as a percentage of income is improving, while consumer debt trends are more concerning. But as always, the headline numbers hide a more complicated story.

Roughly two-thirds of Americans own their homes, but within that majority is a growing divide. Those who locked in ultra-low mortgage rates during the post-pandemic boom are in relatively good shape. The rest face elevated borrowing costs and will be in serious trouble if home prices fall or if they’re forced to move.

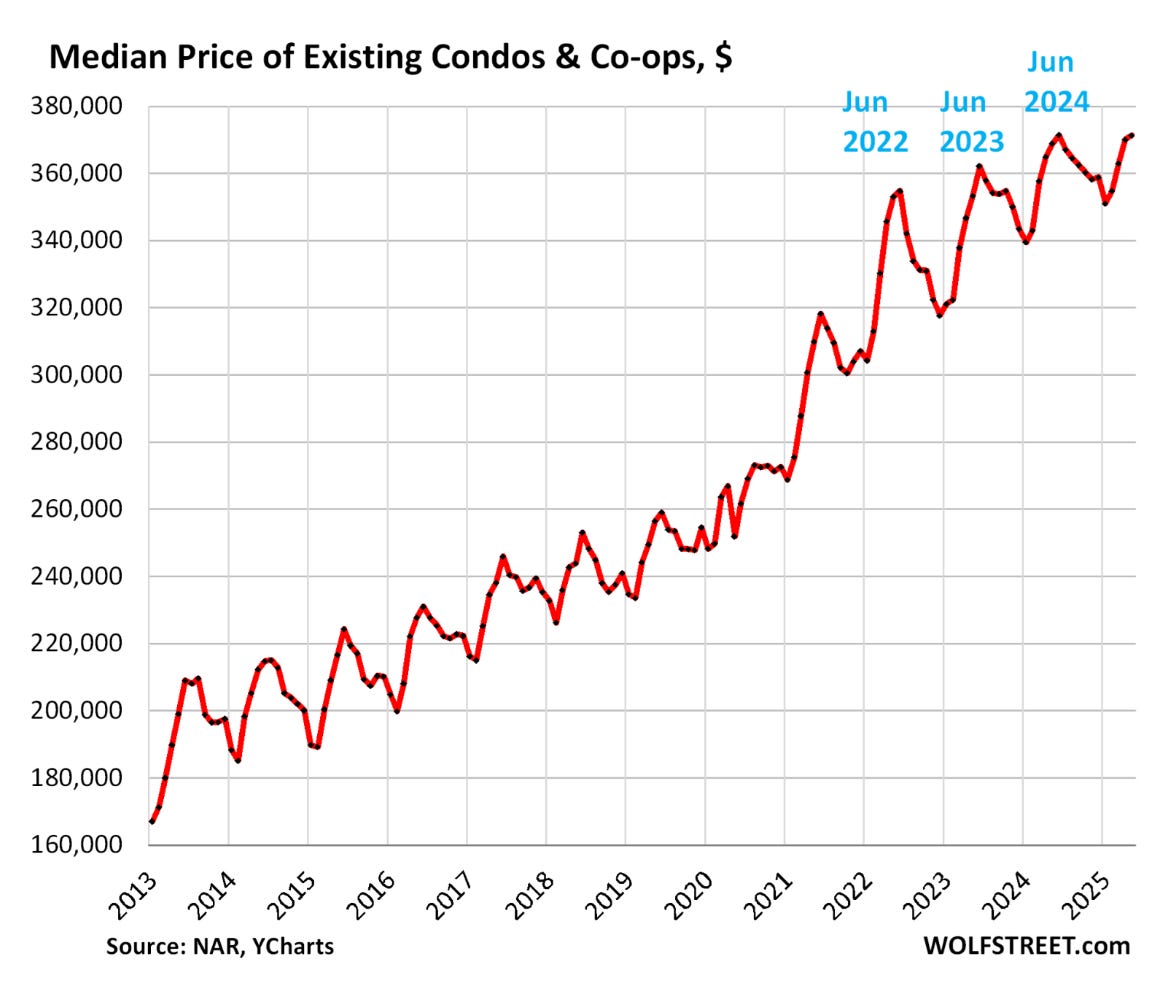

Another red flag: property prices—especially in high-flying urban markets—are correcting. Supply is hitting the market just as affordability vanishes. High rates are locking people in place

Wages are still climbing, but the job market is softening. The work-from-home boom that once justified bidding wars and lifestyle purchases is dead. Fewer households can make the next move. And AI-driven productivity gains, while promising for GDP, do little to alleviate this new economic immobility.

The other one-third of Americans rent. The last few years have been difficult, and their personal balance sheets are in poor shape.

In a large part, “healthy” personal balance sheets are heavily dependent on whether you own your home and what your mortgage rate is. It’s that simple for much of the middle and lower classes.

Which raises another question. What about home prices, and will inflation help propel those to new highs? We will address this specifically in Part 3, but it does appear to be an increasingly difficult lift depending on your home’s “quintile” and location.

It should be no secret that Trump intends to “buy mid-term votes” through favorable crypto policies, the wealth effect (Nico’s explanation here), and tax cuts. This is slightly more palatable than the prior administration, which utilized open borders and debt deferment/forgiveness (my opinion). The debt payment that was halted during the pandemic will again have consequences—leaving the “have-nots” facing tough choices.

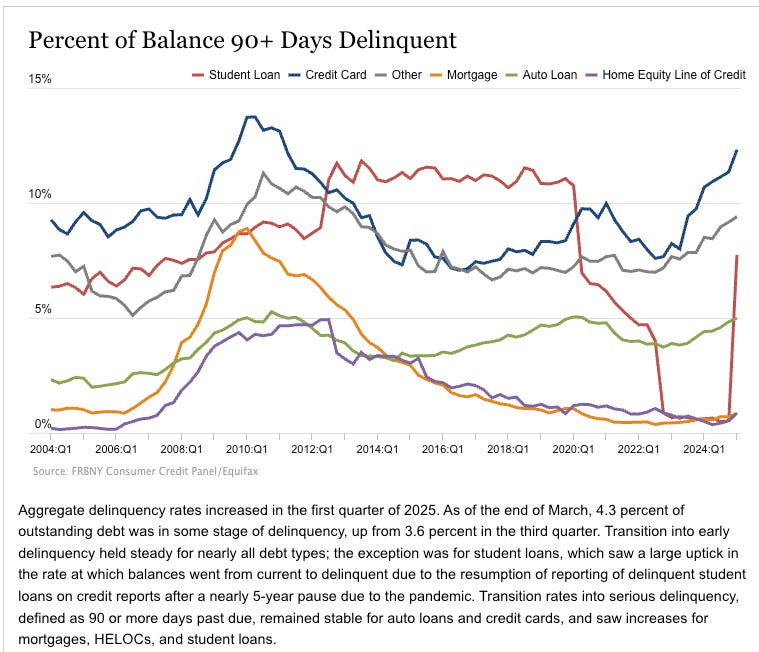

Are Delinquency Rates a Big Deal?

In general, no. Now, maybe yes. Let me explain.

Mortgage defaults—the largest component of private debt—remain near all-time lows. As long as housing prices stay elevated and we avoid a recession that triggers widespread job losses, this won't be a major issue until more mortgages begin to reset. For context, the average American holds a mortgage for about 10 years.

As the chart below shows, student loan delinquencies jumped sharply after the government ended the pandemic-era moratorium on payments. Credit card and “other” delinquencies are also climbing. It's likely there's overlap among these categories.

This helps explain why delinquency rates don’t pose a broad systemic risk right now—but they do matter within specific, vulnerable groups. These individuals are likely renters or mortgage holders underwater and often carry a mix of credit card, auto, and student loan debt. While not the majority, this group represents a significant part of the consumer economy—and they tend to spend.

Mortgages, Interest Rates, and

It’s not hard to see why the risk-free rate matters so much at a household level. Americans who locked in mortgage rates below 3.5% have benefited immensely. Their home values have surged, while their monthly payments stayed fixed—meaning their housing costs have fallen as a percentage of income. That’s a major improvement in personal finances. And if they also held some stocks or crypto, even better.

Home prices have climbed roughly 50% since 2020. The only other periods with similar gains were from 1942 to 1947, when returning soldiers and the GI Bill fueled demand, and from 2002 to 2007, right before the housing bubble burst.

Even within the middle class, the gap between the haves and have-nots is widening. As inflation rises, those without assets—especially real estate—are at risk of slipping into the lower middle class or even toward subsistence living.

This also helps explain why the average age of homeownership is 58 years old and 38 for first-time buyers. Homeownership feels completely out of reach for many young people, leaving an entire generation feeling like they’ve already missed the boat.

In summary, personal and consumer debt is not an immediate threat. Barring a sharp rise in unemployment, we likely have another 3–5 years before it becomes a broader economic concern. Even a dip in home prices will benefit some by attracting new buyers. The real issue in housing has been supply — and that’s finally improving.

Now let’s talk about the big one: Federal Debt. For the sake of time, we’ll skip over state and municipal debt, though it’s worth noting that those are are a time bomb of sorts, too.

States like Connecticut ($27K), New Jersey ($24K), Hawaii ($19.4K), and Illinois ($19.4K) have the highest per capita debt and are almost certain to face tax hikes in the years ahead. Unlike the federal government, these states can’t print their own money. That means eventually they’ll be forced to get closer to a balanced budget — either by raising taxes or cutting spending. For context, California carries the largest total debt at $507 billion.

Is the US Federal Debt on the Clock?

This handy website (USDebtClock.org) tracks a live tally of everything from national debt and money supply to federal outlays and border encounters. The U.S. just crossed the $37 trillion mark in total debt this past week—congratulations, new level achieved 🎉🥳🎉

Except… this isn’t a milestone worth celebrating, hence the recent downgrade.

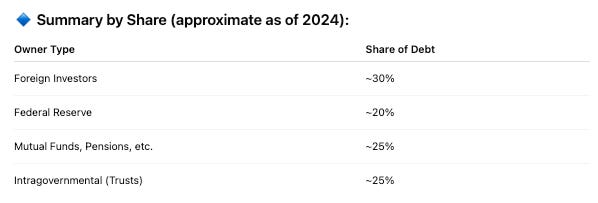

Here are some interesting facts about who owns US debt.

Japan remains the largest foreign holder at $1.13 trillion, though it trimmed positions in April and May. This is a frequent tactic for the central bank that has become the poster-child for loose monetary policy and rising debt.

The U.K. has now overtaken China as the second-largest foreign creditor as of June 2025.

Taiwan’s insurance companies have become controversial holders of US Treasuries due to the size of their savings in recent years. The island saw its currency spike in May, a tacit acknowledgement that it wanted to avoid the currency manipulator tag.

China’s official holdings have dropped to around $760 billion, though true exposure may be higher through intermediaries. Notably, there's no confirmed evidence of outright selling during Trade War 2.0 — despite claims that china was “dumping bonds.”

U.S. entitlement programs hold about 25% of the debt (via Social Security, Medicare, etc.), while the Federal Reserve owns roughly 20%. The Fed’s balance sheet has contracted over $2 trillion since its pandemic-era peak, marking one of the more aggressive periods of quantitative tightening in history.

How Much Debt is Too Much?

There’s no formal constraint on a sovereign government printing its own money. But when it comes to managing debt, the options are fairly simple:

Deflate it

Inflate it

Grow out of it

The third option is the most attractive in theory, but often the hardest to execute in practice. High debt levels, by their nature, weigh on growth prospects through higher interest costs and risk premiums. As debt climbs, so does perceived country risk—raising borrowing costs and forcing the so-called "risk-free" rate higher, pulling every other rate along with it.

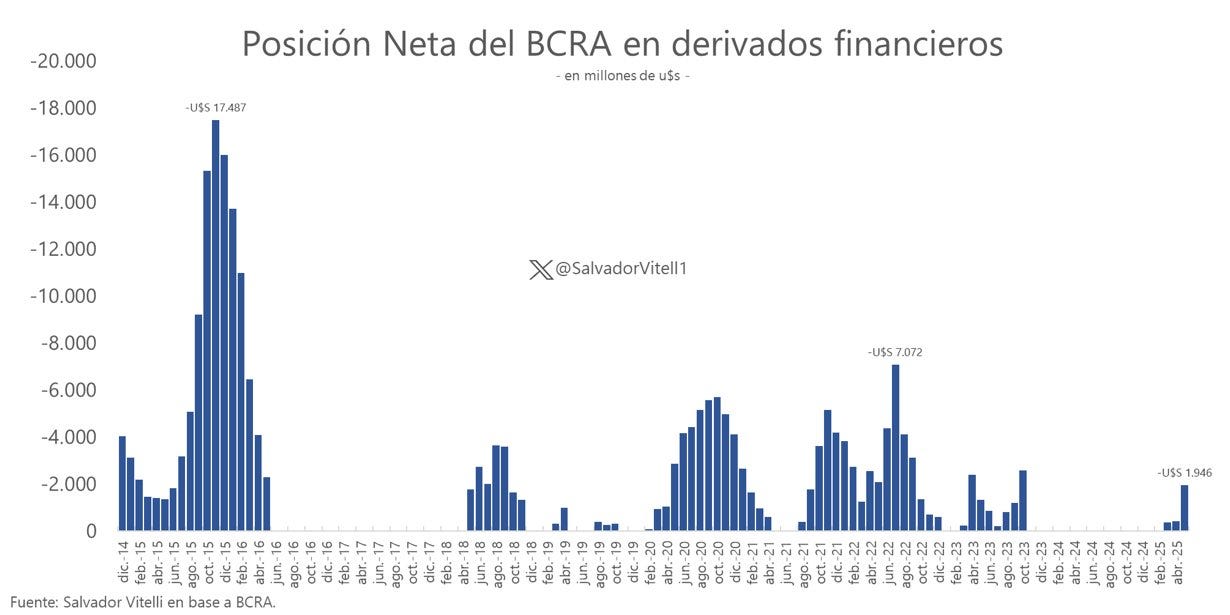

Deflation is the least likely path—politically toxic and painful. As we’ve covered previously, it’s rarely chosen willingly. Argentina’s Javier Milei is a rare example of someone who tried.

The idea: shrink the state’s role, endure short-term pain, and allow the private sector to reallocate capital more efficiently. It’s a brutal deleveraging process, and it only works if the population is willing to suffer through it.

Argentina had few options and found rock bottom. Deflating debt is not a choice any leader willingly makes until it is the last option.

Since the pandemic, federal spending has become the primary engine of demand. That’s not going to change unless it’s forced to.

Enter Trump and Bessent. Their pitch—like many before—is to reduce the deficit through growth. But with no plans to cut spending, they’re left with one lever: YUGE expansion.

Here’s the problem. Their growth plan is incredibly expensive. So even if you get GDP growth and rising asset prices, the deficit continues to outpace tax receipts.

Not all growth is created equal. Productive growth — like infrastructure that creates jobs, facilitates commerce, and boosts economic mobility — propels what’s known as a multiplier effect. Spending a trillion dollars on a Golden Dome or space weapons that collect dust? Not so much.

If the Navy builds ships with multipurpose utility, that's an investment. But if we’re spending $300 million per aircraft that may never see combat, that’s deterrence and deadweight.

To answer the question specifically, there are two ratios that matter.

Debt-to-GDP (annual), which stands at about 100%. Historically, country risk rises above 120/130%, but the US reserve currency status provides much more leeway. The US still has room here.

The other metric is the annual deficit-to-GDP. This is getting far more concerning at 6.2% of GDP. This number will be closer to 7% on its current pace — only the pandemic and the Great Financial Crisis were worse since WWII.

It’s clear the private debt situation isn’t great, but manageable for now. Households, while stretched in certain segments, are not yet showing signs of widespread stress. The real concern is on the public side. Federal debt levels are not just high—they’re structurally reliant on continued deficit spending to maintain baseline growth.

And policymakers must know this. So what are they doing about it?

This Administration’s Ideas are Mostly Gimmicky & Harm Trust — Just Like the Last

Here are a few of the different ways officials from this administration have proposed lowering the debt burden.

Sovereign Wealth Fund

Foreign Direct Investment to fuel the needed growth and industry expansion

Cutting interest rates to pay less interest on debt

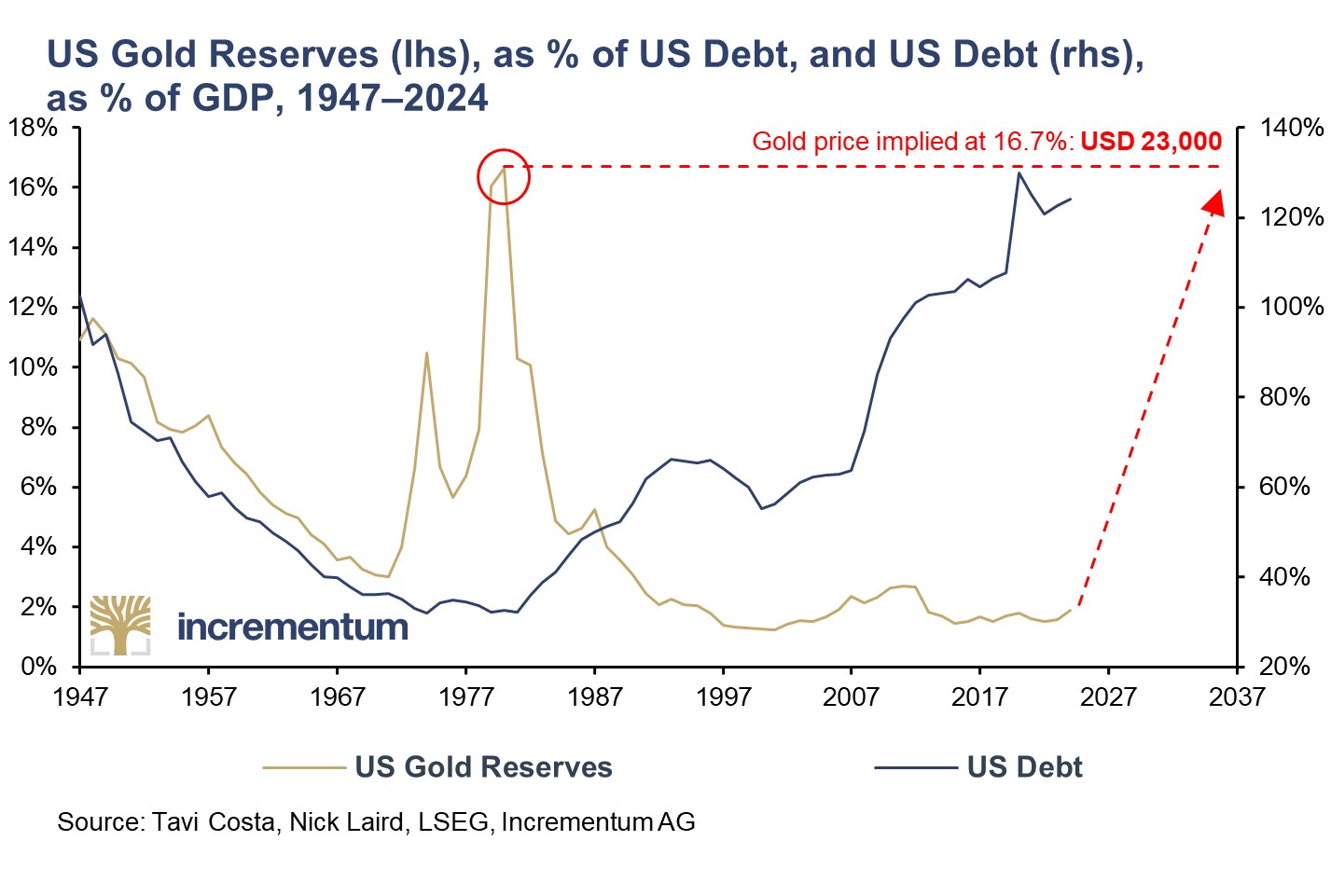

Revaluing the US gold (currently $42/oz)

Selling off federal lands for housing or private investment

Stablecoins to offer more flexible debt servicing

While I’m sure I’ve overlooked a few ideas, I have to say that most of these are terrible suggestions. Breaking them all down here would take too long, and frankly, it’s not worth the exercise.

Sovereign Wealth Funds exist to allocate excess national savings in ways that serve the public good or align with state interests. Trying to speculate your way out from under a mountain of debt feels less like policy — and more like putting it all on black.

Revaluing gold just to enable more government spending signals to the world that the U.S. does not intend to address its structural imbalances. If anything, it risks further eroding trust, especially among foreign holders of U.S. assets.

Yes, the U.S. is the largest holder of gold globally. But here’s the reality: gold would need to skyrocket in value to make even a dent in our debt load. And while many point to a gold standard as a solution, let’s not forget that abandoning it allowed the credit expansion behind America’s post-1970s boom. This isn’t a simple "gold good, fiat bad" debate — at best, gold is a small part of any solution.

The only real solution is to reduce spending and boost revenue through genuine growth, and the tax receipts that come with it. Unfortunately, that path looks increasingly unlikely. So, for now, we’ll keep building upon our thesis and preparing to ensure our clients stay profitable.

Financial markets move through cycles — driven by politics, business dynamics, inflation, and debt. As we enter the later innings of the current debt and political cycle, preparation becomes not just another task, but essential.

Thank you for reading. Please reach out to Nico@archaiq.ai with any suggestions on how to improve our products or if you're interested in exploring new opportunities with ArchaiQ. Sign up for our free weekly newsletter at www.archaiq.ai. Each morning, we will add some daily notes to our Substack chat (link here).

This is not trading or investment advice. Trading Futures is a high-risk activity; please consult with a professional.